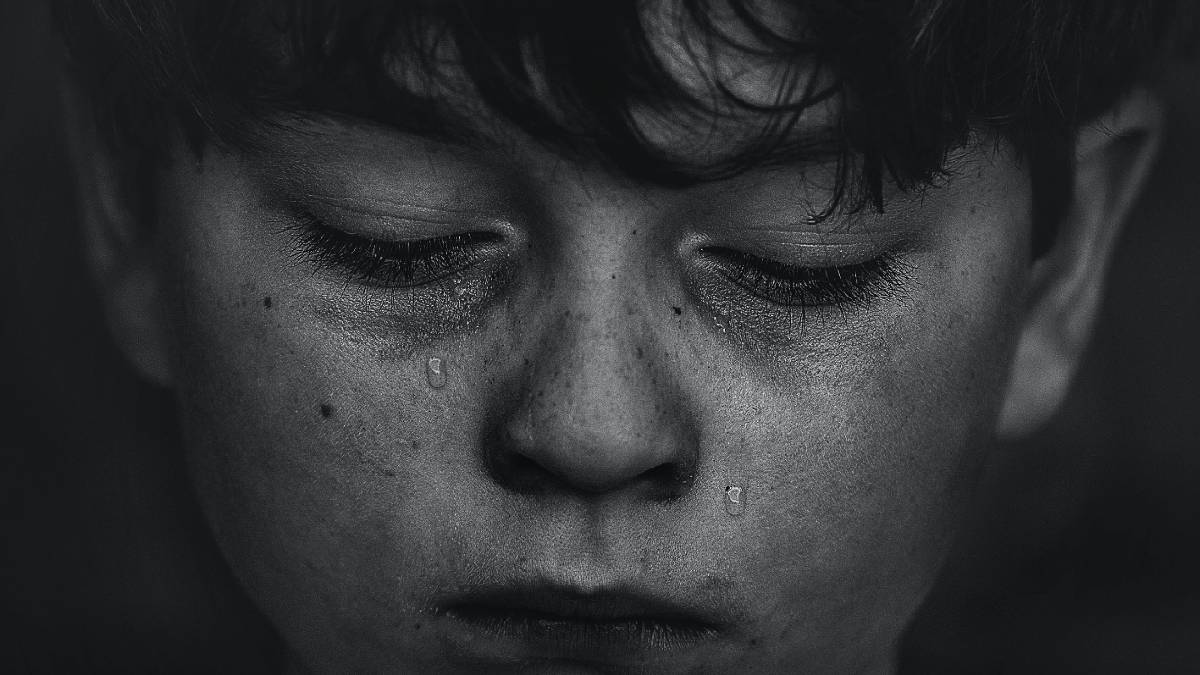

How Painful Childhood Experiences Impact The Way We See The World Today

Psychologists explore differences in decision making styles among people who experienced abuse as a child.

By Mark Travers, Ph.D. | March 28, 2022

A new study published in the journal of Psychological and Cognitive Sciences explores the impact of adverse childhood experiences, i.e., extreme stressors that occur between the age of 0-18, on cognitive development. The study notes that people who have been through adverse childhood experiences are more likely to show certain cognitive deficits, specifically in the area of decision making, as adults.

To better understand the findings, I recently spoke to Alexander Lloyd, a researcher at the Department of Psychology, University of London. Here is the summary of our conversation:

What inspired you to investigate the topic of adverse childhood experiences and their connection with reward feedback, how did you study it, and what did you find?

I have had a longstanding interest in the effects of trauma which stems from my time working with young people in the criminal justice system, many of whom had experiences of adversity during childhood. I was inspired by my professional experience to gain a better understanding of how adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) introduce patterns into decision-making that may lead to negative outcomes, such as criminal justice involvement or psychopathology. There has been a large body of research on the links between adverse childhood experiences and the development of the brain. However, less research has examined the impact of these experiences on how we process rewards. This is notable, as the ability to process rewards has been linked with a number of outcomes in adulthood including substance use and psychopathology.

In order to study the link between adverse childhood experiences and reward feedback, we used a task known as 'patch foraging'. In this task, the individual chooses between staying with a patch where the rewards are known but diminish over time and exploring a new patch with unknown rewards. In our task, individuals had to collect apples from trees; the longer they stayed with their current tree, the fewer apples would be available to collect. Alternatively, they could leave to travel to a new tree which had a fresh bunch of apples. Using this task we were able to calculate how much weight individuals place on recent reward feedback versus more historic feedback (i.e., their sensitivity to reward feedback).

Our findings demonstrated two key things:

- First, adverse childhood experiences were associated with less exploration on our task, meaning individuals with adverse childhood experiences were less successful at taking advantage of the full set of rewards in their surroundings.

- Secondly, we found that the reduced exploration displayed by adverse childhood experience-exposed individuals was associated with underweighting reward feedback.

We hope these findings will contribute to our understanding of the negative impacts associated with adverse childhood experiences and may inform future studies that aim to support those who have experienced adversity.

Can you describe briefly what all are included in adverse childhood experiences?

Adverse Childhood Experiences are extreme stressors that occur between the ages of 0-18. Typically, they are split into three main categories:

- Threatening events, which includes physical abuse, emotional abuse, and sexual abuse

- Neglect, including physical and emotional neglect

- And family adversity, which includes parental divorce, parental substance abuse, mental illness within the household, and having an incarcerated relative

How do you define reward feedback in this case?

In our task, reward feedback is defined as the weight an individual places on recent versus more historic experiences, which is known as their 'learning rate.' To give an analogy: imagine it was Saturday and you are deciding on your plans for Sunday. You are deciding whether the weather will be good enough to do something outdoors or indoors (without checking the weather forecast). Somebody with a high learning rate would only think about what the weather was like on Friday (i.e., only taking their most recent experiences into account) whereas someone with a low learning rate would think about what the weather had been like all week (i.e., taking more historic experiences into account). If you take this example and apply it to situations where it is possible to gain a reward, this 'learning rate' measures how sensitive we are to recent reward feedback.

What according to your research triggers underweighting reward feedback in adulthood after experiencing adverse childhood experiences?

We cannot conclude whether adverse childhood experiences trigger underweighting of reward feedback from our study due to the cross-sectional design. However, we think that our findings may be linked to the development of regions of the brain that are responsible for processing rewards, as previous research has found that individuals who have experienced adverse childhood experiences have less neural activation in response to rewards compared to individuals without these experiences. Some recent studies have also found that adverse childhood experiences are associated with a difficulty learning the connection between actions and the rewards that result from those actions, which may also play a part in why individuals with adverse childhood experiences underweighted reward feedback in our study.

What are the practical takeaways from your research for someone who has been through adverse childhood experiences and is facing this challenge?

Practically, I think it would be important to understand that individuals with these adverse childhood experiences may not respond to positive scenarios in the same way to people without these experiences. So, for people with experiences of trauma, it may be that they aren't as quick to recognize positive opportunities in their surroundings. We also found that people who had experienced adversity were less likely than people without these experiences to explore their surroundings, so it may be the case that individuals with adverse childhood experiences find it difficult to try new opportunities.

Did something unexpected emerge from your research? Something beyond the hypothesis?

We actually had quite a few surprises with this research. Initially, we expected that people who had experienced adverse childhood experiences would have a higher learning rate because this can be helpful in unpredictable environments, which are characteristic of adverse childhood conditions. However, our results went in the opposite way and we instead found that individuals with adverse childhood experiences underweighted reward feedback. Something else that we did not explicitly predict was that individuals with adverse childhood experiences would collect fewer rewards from their environment, which we think is important for understanding how childhood adversity is associated with gauging the value of exploring new opportunities. In our task, this was how often people explored new trees but this could be related to how people estimate the value of trialing new experiences, such as going to new places or seeking out new job opportunities.

Did demographics including gender play a role in perceiving feedback in adulthood?

We did not find any differences between male or female participants, or any association with age and reward feedback. However, in our previous work, we have found that adolescents explore more than adults on this foraging task, so it would be interesting for future studies to examine how adolescents with experiences of adversity approach the task compared to adolescents without experiences of adversity.

How should professionals including therapists deal with people who have had adverse childhood experiences and now are facing this challenge?

We found that individuals who had experienced adverse childhood experiences were less likely to explore new opportunities compared to individuals without these experiences. As such, it could be helpful for professionals working with people with adverse childhood experiences to understand that experiences of adversity can be associated with a reluctance to trial new things, which may make certain interventions more difficult for people with these experiences. Our research also suggests that individuals with adverse childhood experiences underweight reward feedback, so encouraging individuals with adverse childhood experiences to recognize positive reward feedback may also be helpful when supporting somebody with experiences of adversity.

Do you have plans for follow-up research? Where would you like to see research on adverse childhood experiences and reward feedback go in the future?

We are hoping to run a similar study with adolescents who have experienced adversity to see whether we find similar differences in exploration and reward processing. As adolescence is a period of significant social and emotional development, it may be that we can identify a period of adolescence where interventions can be developed to reduce the impact of adversity on later outcomes. Ultimately, I would like to see future research develop interventions to reduce the mental health impacts of adversity by identifying features of cognition that are impacted by these experiences. This work is hugely important given that a substantial body of research has demonstrated that early adversity is associated with negative social, emotional, and physical outcomes in adulthood.