What The 'Ben Franklin Effect' Reveals About Getting People To Like You

It sounds backwards, but doing less for others and asking them to do more for you can dramatically boost connection.

By Mark Travers, Ph.D. | December 1, 2025

Most of us assume that warmth is what leads to generosity, rather than the other way around. It's an intuitive order of events: we like people first and then choose to help them. However, according to research from the Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, the opposite can also be just as true. Intriguingly, this is what's known as the "Ben Franklin effect": when after doing someone a favor, you actually begin to like them more, despite having felt neutral or indifferent about them beforehand.

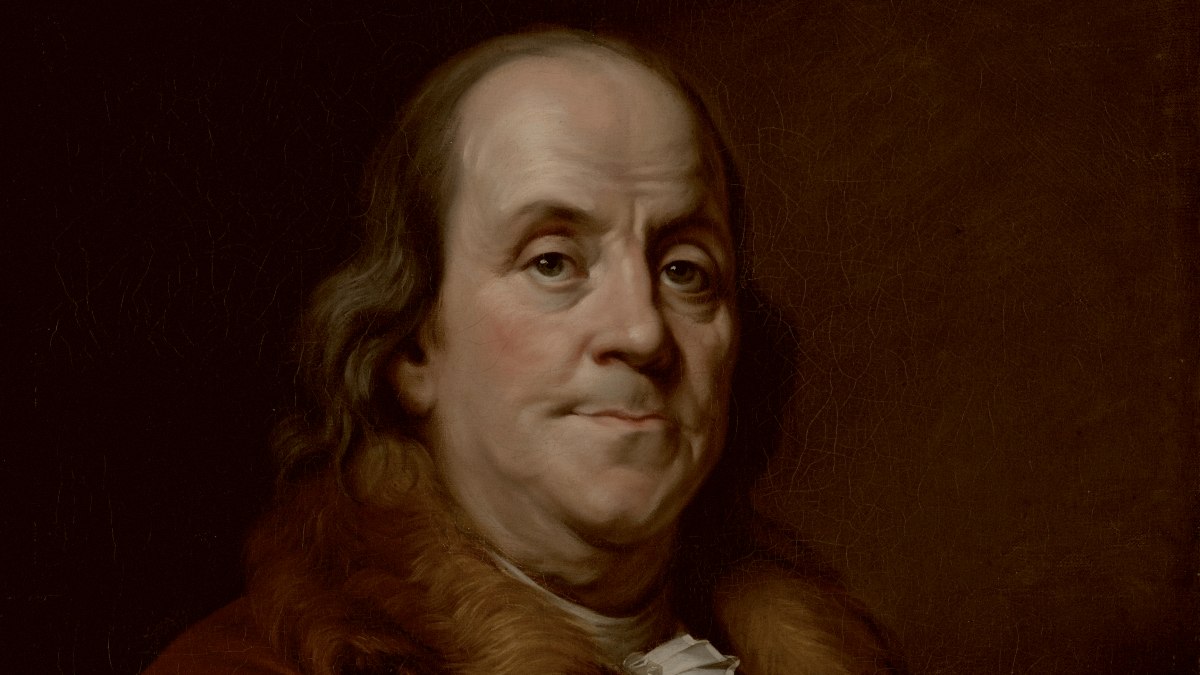

The phenomenon is named after founding father Benjamin Franklin, who famously described using small requests to soften his political rivals. For instance, he once described asking a man to lend him a rare book. His rival agreed, and, from that moment on, the man became significantly more friendly toward Franklin; he actively sought both his company and goodwill.

Here's a breakdown of how this high-leverage psychological effect works, as well as how you can start using it to your advantage.

The Psychology Behind The 'Ben Franklin Effect'

As the abovementioned study notes, psychologists eventually identified that the cognitive mechanism underlying this counterintuitive social shift was, in fact, cognitive dissonance. In simple terms, cognitive dissonance occurs when our behaviors don't align with our beliefs. In turn, our minds unconsciously adjust our attitudes in order to reduce the discomfort this misalignment brings on.

In terms of the Ben Franklin effect, this means that if you help someone that you feel either neutral or negative toward, your brain is likely to try and reason: "Well, I wouldn't go out of my way for someone I dislike — so I must like them." This mental correction is what makes the effect so immensely impactful, as it has enormous implications for our rapports and trust.

The concept gained significant scientific traction after renowned researchers Jon Jecker and David Landy's classic 1969 experiment, published in the journal Human Relations. Specifically, participants within the study who had done a favor for the experimenter or were asked to do one rated the experimenter as much more likable than those who had received a favor or had no interaction at all.

With this study, Jecker and Landy were able to provide proof for the effect: helping someone can indeed make you like them more. This also aligns with decades of prior and subsequent research on cognitive dissonance, which strongly suggests that our behavior is more likely to shape our beliefs than the inverse.

In other words, when we act generously, we unconsciously convince ourselves that we must care for the recipient in some way or another.

How The 'Ben Franklin Effect' Shows Up In Everyday Life

Thankfully, you don't need rare books or political rivals in order to see the Ben Franklin effect in action. If anything, you've likely already experienced it in your own life without even realizing it:

- The workplace. Have you ever offered to help out a coworker, only to find that, suddenly, interacting with them feels smoother? You might've even found yourself rooting for their success. This is because helping others leads us to believe that we've invested in them; in turn, their success is an extension of our own. Notably, this works both ways: asking a colleague for advice can make them feel more connected to you. This is why mentors often feel a deep fondness for mentees who actively seek their guidance, because effort builds emotional stake.

- Friendships and romantic relationships. Favors can reinforce affection in close relationships, from making someone a coffee to helping them move furniture. This isn't because the act itself is meaningful, but because of the internal justifications we make for them. This is why shared effort (i.e., co-parenting, home projects, collaborative problem-solving) can strengthen bonds. It's also why one-sided effort can make you resentful.

- Social and networking dynamics. People enjoy feeling helpful because they enjoy being needed. As such, asking for a favor is, in its own way, a compliment. That moment of usefulness creates connection, as it's one of many ways for you to indicate that you trust someone's judgment. This is why seasoned networkers like Ben Franklin ask for small, meaningful favors, rather than trying to schmooze their way into relationships.

The Ben Franklin Effect suggests that our actions can build connections far more reliably than just our emotions alone. So, instead of waiting to feel closer to someone, asking for a small favor can actively create the closeness we're searching for.

This has implications for romantic relationships, friendships, family dynamics and even healing old wounds. Offering a small favor to someone you feel slightly distant from can be a gentle yet effective way to reopen the connection. However, the inverse is also true: if you never put in effort, your complacency will only create emotional distance.

How To Use The 'Ben Franklin Effect' (Without Being Manipulative)

Using the Ben Franklin effect to your advantage doesn't make you a manipulator. It just means that you've become aware of one of the many unconscious ways that we develop healthy relationships. To make the most of it:

- Start small. Meaningful favors can create the strongest shifts, but only if they're manageable. Think: offering a ride, sharing a resource, giving thoughtful advice or lending an item.

- Ask for help sometimes. It may feel counterintuitive when you try it, but it's ultimately powerful. People feel more connected when they're allowed to contribute. Too much self-sufficiency, on the other hand, can unintentionally push people away.

- Be sincere. The Ben Franklin Effect can only work if you're requesting something in good faith. If your motivation is to manipulate someone, then the psychological benefits won't work.

- Notice the shift. Pay attention to how helping someone changes your feelings toward them. You'll begin to see patterns in how much empathy, interest, investment and warmth you feel toward them.

Ultimately, the Ben Franklin Effect flips our assumptions about generosity. Evidently, we don't just help the people that we like; we start liking the people we help, too. It's one of the most effective and wholesome tools we have for strengthening relationships, deepening trust and building genuine warmth.

Many of us are prone to wait until we naturally "feel closer" to someone before we ask them for something, but this phenomenon invites us to reverse the order. Act first. Offer something small. Ask for something small. Let the feeling come afterward. You may be surprised by how a simple favor can reshape your connections and who you allow into your emotional world.

The Ben Franklin effect relies on your ability to be authentic with others. Take this science-backed test to uncover yours: Authenticity in Relationships Scale

A similar version of this article can also be found on Forbes.com, here.