The Psychology Behind Power-Hungry Leaders

From Hitler to Trump, new research points to early trauma as a common thread in the quest for power.

By Mark Travers, Ph.D. | June 17, 2025

Psychological researchers often assert that leadership styles have deeply personal roots. Narcissistic leadership, in particular, is viewed as one of many products of adverse childhood experiences.

This leadership style is marked by grandiosity, a need for constant admiration, hypersensitivity to criticism and a tendency to dominate. While it may lend to charisma and assertiveness, it may also lend to highly dangerous, destructive regimes. This is especially true when they manifest in the realm of politics.

A May 2025 study published in Frontiers in Psychology sought to explore the early-life origins of what it calls "narcissistic political leadership." Through the cases of Adolf Hitler, Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump, the study examines how particular childhood dynamics may lay the psychological groundwork for power-obsessed leadership styles.

Why Childhood Matters, And Where We Draw The Line

The study does not (and ethically cannot) claim that these men meet the criteria for narcissistic personality disorder. In fact, the Goldwater Rule, a long-standing principle established by the American Psychiatric Association, definitively prohibits psychiatrists from diagnosing public figures that they haven't personally evaluated.

As the study's author, Yusuf Çifci, explains, "It is not possible to apply psychological tests to political leaders, to sit them on Freud's couch and psychoanalyze them. However, it is possible to find detailed information on the childhoods and families of political leaders."

The study is based on exactly that: information from diaries, interviews, family biographies and historical records. Drawing from this material, Çifci identifies early-life patterns of trauma, loss and parenting styles that may help explain the emergence of narcissistic traits in adulthood.

These psychological interpretations offer a lens — not a label — through which we might understand the roots of narcissistic behavior in some of the world's most controversial leaders.

Constructive vs. Reactive Narcissism

Many people implicitly understand the term "narcissism" to carry negative connotations. But, psychologically, not all manifestations of narcissistic traits are inherently pathological. As such, Çifci distinguishes between two broad types in his study: constructive and reactive.

- Constructive narcissism is a normal, healthy product of a stable emotional environment. When children receive appropriate levels of support, challenge and validation, they tend to grow into confident, resilient adults with a secure sense of self. These milestones, as a result, give rise to a grounded self-esteem and a healthy leadership style.

- Reactive narcissism, however, tends to form as a response to neglectful, inconsistent or abusive childhood experiences. In these cases, children may build a grandiose self-image — not necessarily as a product of ego, but rather out of dire psychological necessity. This inflated sense of self serves as a defense mechanism: a buffer against any and all feelings of shame, powerlessness or worthlessness.

Over time, and most especially in environments that reward control and dominance, these defenses may solidify. In environments where image, authority or validation constantly prove valuable (like politics), reactive narcissism may well take on a fixed role in personality.

Çifci identifies four recurring developmental themes in the childhoods of his case subjects:

- An authoritarian, punitive father

- An indulgent or emotionally compensatory mother

- Early trauma or emotional abandonment

- High, unrealistic expectations or pressure

Below, he explores how these patterns played out in the lives of Hitler, Putin and Trump — and how they may have shaped their leadership styles.

1. Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler's childhood was marked by whiplash-inducing emotional dichotomies. His father, Alois Hitler, was authoritarian and prone to physical punishment: he demanded absolute obedience and showed little affection.

Historical accounts, including those from Alice Miller, describe a household ruled by fear. Young Adolf was reportedly beaten regularly and disciplined harshly.

In vast contrast, his mother, Klara, doted on him. Having lost three children before Adolf, she was intensely protective and emotionally dependent on him. Çifci, and many other psychologists, describe Hitler as the epitome of a "replacement child:" unconsciously tasked with filling the void left by their deceased siblings. In Klara's eyes, he may have been the child who had to survive, succeed and redeem the family's pain.

This juxtaposition — between a humiliating, critical father and an adoring, idealizing mother — may have fractured Hitler's developing sense of self. On one hand, Hitler's father instilled in him a deep sense of powerlessness, fear and rage. On the other, his mother instilled grandiosity, entitlement and specialness. Çifci argues that this inner contradiction is what may give rise to reactive narcissism, where a fragile self-worth is propped up by exaggerated fantasies of superiority.

In his rise to power, these wounds played out catastrophically. Hitler surrounded himself with sycophants, had zero tolerance for dissent and demanded unwavering loyalty. He cast critics as traitors and scapegoated entire populations. Even in death, he absolved himself wholly of responsibility. His suicide note blamed everyone but himself: "My generals betrayed me."

Çifci suggests that his enduring pattern of "chronic narcissistic rage" — fury rooted in early psychological trauma — is consistent with a deeply wounded personality driven to dominate in order to feel whole.

2. Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Putin's early life echoed many of the same emotional themes as Hitler's. Born in 1952 in post-war Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), he entered a family already scarred by loss. His parents, much like Hitler's, had lost two sons before him.

His father, a wounded war veteran, was reportedly stern, emotionally distant and physically abusive. His mother, by contrast, was one of few sources of warmth and comfort.

As with Hitler, this offset dynamic of a cold father and nurturing mother (coupled, once again, with "replacement child" status) forms the core of Çifci's analysis.

Putin also grew up in poverty. He was surrounded by the remnants of war and hardship: a rough neighborhood in which dominance and toughness served him well. These early lessons about strength and survival may have instilled in him a need to appear invulnerable at all times.

In adulthood, this may be mirrored in his tightly managed image control. Putin is known for stage-managed displays of hypermasculine prowess: deep-sea diving, hunting, horseback riding, judo, bare-chested adventures in the wilderness. Çifci interprets these as compensatory behaviors — attempts to project the kind of dominance he may have deeply craved as a child.

Çifci asserts that his political style reflects this too: rigid control over media, little tolerance for dissent and an assertive foreign policy.

According to Çifci, these are hallmarks of reactive narcissism built on emotional insecurity: "Putin's political style is the direct result of his uncanny psychological chemistry. In other words, Putin's leadership is also a narcissistic political leadership, and it cannot be evaluated independently of his parents."

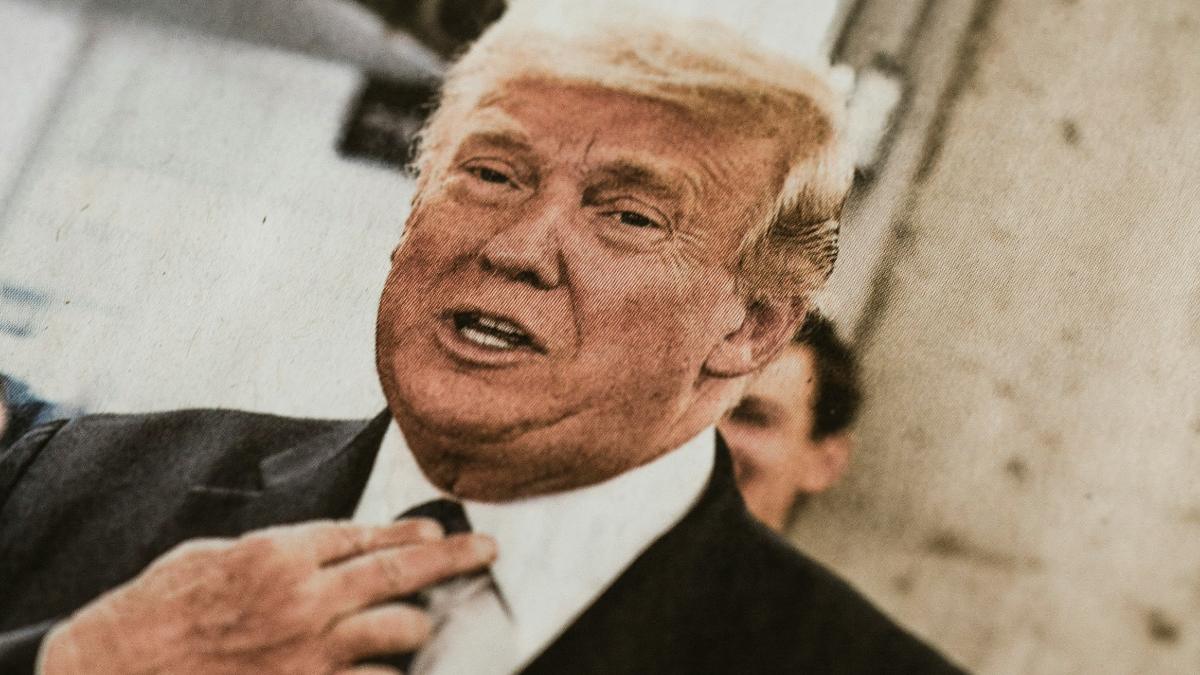

3. Donald Trump

Donald Trump's upbringing shares somewhat similar psychological hallmarks, albeit filtered through the lens of American capitalism. Born in 1946 in Queens, New York, he grew up in a household where power and success were everything.

His father, Fred Trump, was a highly successful real estate tycoon: demanding, emotionally distant and singularly focused on achievement. Trump has described him as a "tough" man who taught him to be a "killer." His mother, Mary, was reportedly affectionate but frequently ill; this made her largely emotionally absent during key phases of his development.

At 13, Donald was abruptly sent away to military school — a disciplinary decision made by his father in response to what he saw as "rough" behavior.

Trump has publicly framed this as a formative experience, but Çifci sees it as a symbolic rejection. In Çifci's words, "It meant falling out of favor, being suddenly expelled from heaven while his brothers and sisters continued to enjoy the family luxuries."

Trump's older brother, Fred Jr., struggled with alcoholism and died young; Trump himself has acknowledged how deeply this affected him. This perceived failure (and its consequences) may have reinforced a family message: success is the only path to love or worth.

Çifci argues that we may be seeing these emotional themes today in the political arena. Trump's rallies, inflammatory language, thin skin toward criticism, obsession with crowd size and media coverage — Çifci suggests these to be symptoms of a personality driven by defensive grandiosity. He believes that Trump demands adoration, and that he likely interprets any and all slights as an existential threat.

In a particularly striking observation, he notes how political cartoons often depicted Trump as a "wounded little boy who wanted to be the most powerful man in the universe as compensation." Çifci writes simply, "The cartoonists… understood him well."

Concerned that you might have narcissistic tendencies? Take this science-backed test to find out if it's cause for concern: Narcissism Scale

A similar version of this article can also be found on Forbes.com, here.